|

|

South Atlantic Council

|

No. 14 |

DELIMITATION OF THE ARGENTINE CONTINENTAL SHELF

|

Updated |

Short SummaryThe Argentine Foreign Ministry announced on 28 March 2016 that it had gained international recognition of a claim to an exceptionally large continental shelf. But they were mistaken. Argentina had made a submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) on 21 April 2009 to claim sovereignty rights over the resources of the sea-bed. The claim covered all the shelf that spreads hundreds of miles to the east and south of Argentina. This included the disputed territories of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands that all sit on the continental shelf, far from the Argentine mainland. The claim also covered a section of the Antarctic continental shelf, an area where no government can exercise sovereignty. On 23 May 2016, the Commission made public its recommendations and only a small proportion of the Argentine claim was endorsed. This paper explains the legal regime and the political process that led the Commission to refuse to consider the Argentine claim to the shelf around the islands controlled by the United Kingdom, and to a part of Antarctica. The continental shelf can be understood as the continuation of the coastal land mass into relatively shallow seas, before the deep oceans are reached. It usually spreads out as a gently sloping area, until it drops sharply at the continental slope. The boundary of the shelf is defined in terms of the foot of the slope or the line where the depth reaches 2,500 metres or where the sediments from the coast thin out. It requires a great deal of scientific investigation to establish which of the criteria apply and where the boundary lies. The matter is simplified to some extent, by allowing all coastal states a minimum legal shelf of 200 NM (even if the geology does not justify it). There are also two alternative maximum limits. The international law on the continental shelf is embedded in a major global treaty, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). It defines the role and the status of the Commission. UNCLOS also declares the Commission’s recommendations are to be “final and binding”. The Commission is composed of 21 scientists and each submission is examined by a sub-commission of seven Commission members. The Convention and the CLCS Rules of Procedure forbid these scientists from making any decisions about legal or political disputes. For this reason, the Commission instructed the sub-commission on the Argentine submission not to consider the shelf around the disputed islands. In 1957-59, Argentina and Britain were among the twelve governments that set up scientific programmes in Antarctica for an International Geophysical Year. This led to the 1959 Antarctic Treaty, which suspended all claims to sovereignty in Antarctica. With the addition of other legal arrangements, this grew into the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), which created a global science observatory and wildlife reserve. In November 2004, Australia became the first country to claim a continental shelf in Antarctica. Governments divided into two groups on the question of how to ensure compatibility between UNCLOS and the ATS. However, they were united in arguing the Commission should not consider any claims. One group wanted restrictions “for the time being” and the other wanted permanent restrictions on any sovereignty rights. The sub-commission on the Australian submission was instructed in April 2005 not to consider a boundary for the Australian claim to part of Antarctica. Following such a precedent, the Commission had no choice but to refuse to consider the Argentine claim to a different part of Antarctica. In April 2010, there were two other cases directly relevant to the Argentine submission. The Commission refused to establish a sub-commission to consider the British partial submission on the Falklands and on South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, due to the dispute with Argentina. The Commission also responded to a Norwegian submission on Bouvet Island and Queen Maud Land (part of the main Antarctic land mass). It did establish a sub-commission, but instructed it only to consider Bouvet Island. In this context, it is not surprising that the Commission decided, in August 2009, in relation to the Argentine submission, that it could consider neither the disputed islands nor Antarctica. When the Argentine submission came to the head of the queue in August 2012 and a sub-commission was established, these decisions were reaffirmed. The recommendations on Argentina were finalised by the sub-commission in August 2015; confirmed by the full Commission on 11 March 2016; and sent to the Argentine government just over two weeks later. The Foreign Ministry publicised a map on 28 March suggesting the whole Argentine submission had been endorsed. The Argentine and British press produced incorrect headlines about the UN approving Argentine claims to sovereignty over the Falklands. Nothing remotely justified these headlines. The maps released on 23 May 2016, in the Commission’s Summary of the Recommendations show two sectors had been endorsed. The first runs, from the Rio de la Plata boundary with Uruguay, south to the boundary of the waters around the Falklands. The other is a tiny area south of Tierra del Fuego and Staten Island. All data about the shelf around the disputed islands and adjacent to Antarctica was completely ignored and no boundaries for these areas were endorsed. It remains a mystery how professional staff in the Argentine Foreign Ministry could fail to appreciate what was happening in the Commission. It was clear for over six and a half years, from August 2009 to March 2016 that the Commission would not and could not approve the whole submission. An even more important question for the Argentine political system is to ask how the Foreign Minister, Susana Malcorra, and her Deputy, Carlos Foradori, were so misled by the diplomats. The South Atlantic Council was formed to promote communication between Argentines, British people and Falkland Islanders, in order to seek co-operation and understanding that might eventually lead to a peaceful settlement, to the Falklands/Malvinas dispute, acceptable to all three parties. Neither Britain nor Argentina can separately gain any internationally recognised rights to exploit the resources of the continental shelf, in the south-west Atlantic, so long as the dispute continues. On the other hand, the Commission could endorse a joint submission, if the governments of Argentina and the UK were willing to agree pragmatic arrangements to share the resources. This story demonstrates how pointless it is to continue with ritualised conflict, based on a nineteenth century idea of sovereignty. |

IntroductionIn April 2009, Argentina submitted a claim for recognition of an extensive continental shelf and the right to control the resources of the shelf in the southern Atlantic Ocean. This claim was considered by the legally-responsible international body, the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), and, in March 2016, the Argentine government announced its submission had been approved. It was widely reported in the news media as meaning the United Nations had recognised an Argentine claim to the waters around the Falkland Islands. While it is true the Argentine submission was approved, the release of the Commission’s Summary of the Recommendations on 23 May 2016 shows it is not true that the CLCS approved any limits to the shelf derived from the dispute about the Falkland Islands nor other disputed islands nor Antarctica. This paper will outline how a coastal country gains international recognition of its continental shelf and how the news reporting on the Argentine claim was substantially incorrect.

Defining the Width of the Continental ShelfAs knowledge of what resources are available from the seas has expanded and as the technology to exploit those resources have improved, governments of coastal states have wanted to claim control over the widest possible band of the waters around their coasts. All significant aspects of the use of the seas now come under an international treaty, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which was agreed and signed in 1982. This has established four borders, delimiting four areas of the seas over which each coastal state has rights.[1]

|

|

|

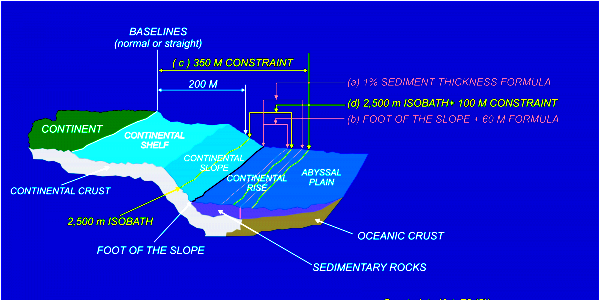

The idea of the continental shelf, as the natural geological extension of a country’s land below the sea, is easy to understand, but defining its boundary is very complicated. Geologists refer to three areas:

|

|

| Source: COPLA, Continental Shelf Graphic. |

|

UNCLOS provided a political solution to reduce substantially (but not eliminate) the need for production of extensive and detailed geological maps. All countries would have legal rights to a “shelf” extending to a minimum of 200 NM from the coast, whether or not a geological shelf actually exists. In addition, two maxima were set and whichever is the longest distance can be applied – the shelf can go up to 350 NM from the coast or up to 100 NM from the line marking a depth of 2,500 metres (the 2,500 m isobath).[3] For Argentina, on the Patagonian Shelf, both the two maxima and the minimum apply. In addition, each of the different geological criteria apply. Starting from Rio de la Plata boundary with Uruguayan waters, the foot of the continental slope is defined by the sediments becoming thinner. Further south, the 350 NM maximum applies. Then, the alternative maximum applies and the boundary becomes 100 NM from the 2,500 m isobath. In the extreme south, the boundary south-east from Isla de los Estados (Staten Island) is the minimum of 200 NM from the coast. Finally, there is a small sector up to the maritime boundary with Chile that is 60 NM from the foot of the slope, defined by the greatest change in its gradient.[4]

The Role of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS)When a government wishes to exercise sovereignty over the resources of the sea-bed and its sub-soil beyond the EEZ, UNCLOS requires it to submit detailed, scientific information for evaluation by a Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). The Commission is composed of independent, expert scientists, but at the same time it has a political structure. No two individuals can be of the same nationality; they are nominated by governments; and each of the five geographical groups that caucus in global diplomacy must have at least three members.

If a coastal state does wish to establish rights to a continental shelf beyond the minimum of 200 NM, it must take the initiative and submit charts plotting the shelf boundary, along with echo soundings, seismic tests and geophysical data, to support the claim. Then, a sub-commission of seven members is appointed. The members of the sub-commission cannot be nationals of the coastal state nor any Commission members who have provided advice on the application. After a lengthy process of considering all the data, the sub-commission makes a recommendation to the full Commission. If the Commission approves the recommendation, the government can deposit the final definitive charts, with the UN Secretary-General.[6] There are stringent conditions in the CLCS Rules of Procedure for maintaining the confidentiality of the data, presumably because it might have commercial significance. When a submission is received, only an Executive Summary is published. After a submission is accepted, only the charts and geodetic data (defining the shape of the sea-bed) must be made public. The deliberations of the Commission and its sub-commissions take place in private and remain confidential. Normally in the UN system, records of meetings are published, either verbatim or in a detailed summary. In the case of the CLCS, its deliberations remain secret and only the formal decision becomes public, in a statement by the chair of each session on the “Progress of Work in the Commission”. The privacy of meetings not only maintains confidentiality, but also minimises pressures upon the members of the Commission. Governments can make summary presentations on their case, in public, when a submission is first considered, and they can be invited to make “clarifications”, but they cannot be represented when recommendations are being discussed.[7] When the recommendation on the first submission, (by Russia), came before the CLCS, the UN Assistant-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs commented

At the same meeting, one Commission member argued for a Russian delegation to be present when the recommendations on their submission were being considered. The Chair argued the Rules required the deliberations to be in private. The question had to be put to a vote and the Russian request was rejected by fifteen votes to three (with three members absent).[8] Each coastal state had a time limit of ten years after becoming a party to UNCLOS, by which they must make their submission. The members of the Commission were elected in March 1997 and they started work in June 1997. Initially the CLCS had to define its procedures: in particular it had to specify its Scientific and Technical Guidelines on how submissions should be made. The Guidelines were adopted on 13 May 1999 and the first submission was made, by Russia, on 20 December 2001. It was clear that many countries, particularly developing countries, would not be able to meet the deadline of November 2004 for their submissions. Led by the members of the Pacific Island Forum, they proposed an extension of the deadline. In May 2001, a Meeting of the States Parties decided the ten-year period would start from when the Guidelines had been adopted, for any countries that had become parties before this date.[9]

The Legal Status of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental ShelfAlthough the text of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea was signed by 119 governments in December 1982, it could not enter into force until one year after the sixtieth state had ratified or acceded to it. This occurred more than a decade later, on 16 November 1994. After that date, it has entered into force for any other state 30 days after they have ratified or acceded. In 1982, the US government refused to sign the Convention and they still have not done so, because they opposed the provisions for an International Sea-Bed Authority to regulate the resources of the sea-bed in the deep seas beyond the legal boundaries of each continental shelf. The United Kingdom Conservative governments of the 1980s and the 1990s adopted the same policy. The Argentine government had a variety of concerns about the Convention, in particular they strongly objected to Resolution III in the Final Act of the UN conference. This covered the application of the Convention to colonial territories and referred to the rights of the people, even where a dispute exists about sovereignty.[10] Argentina delayed signing the Convention until October 1984, and then did not proceed with ratification for another eleven years. Consequently, neither Argentina nor the UK were among the original parties to UNCLOS. Argentina changed its policy under President Menem. An agreement with Britain, in November 1990, led to the creation of a bilateral South Atlantic Fisheries Commission and a further agreement in September 1995 brought exploration for hydrocarbons under a Joint Commission on Offshore Activities. A few weeks later, Argentina ratified UNCLOS, but with a strong reservation rejecting any connection between the main Convention and the Resolution on colonial territories. In Britain, policy on UNCLOS did not change until the formation in 1997 of a Labour government, which quickly acceded to the Convention. UNCLOS entered into force for Argentina on 31 December 1995 and for the UK on 24 August 1997. Consequently, for both countries, their deadline for making submissions was 13 May 2009, the end of the extended ten-year period. Currently there are 168 parties to UNCLOS, but 29 members of the UN have not become parties: fifteen are small land-locked states and fourteen are coastal states whose governments have various political objections.[11] All the provisions of UNCLOS are binding on all the parties to the Convention, including both Argentina and the UK. Most international lawyers even argue UNCLOS is binding on all other states that have not become parties to it, because its provisions now have the status of customary international law.[12] The Commission has been widely referred to as being part of the United Nations, but it is not. It has the same status within the UN system as many subsidiary bodies of disarmament, environmental and human rights agreements that are set up by separate treaties. These bodies are often serviced by the UN Secretariat, sometimes under a separate budget and sometimes, as for the CLCS, under the UN’s regular budget. The distinction between treaty bodies and UN bodies is not just a technical point. As noted above, the UNCLOS parties do not include all 193 UN members. In addition, four non-members of the UN are parties to UNCLOS.[13] The treaty bodies, such as the CLCS, are elected by and come under the authority of the meetings of UNCLOS parties. The CLCS does not report to any UN body. The “recommendations” of the CLCS have greater legal weight, under the articles of the Convention, than do “recommendations” of the UN General Assembly, under the articles of the UN Charter.

The Legal Status of the Commission’s RecommendationsThe British government has been widely quoted in the press as saying “It is important to note that this is an advisory commission that makes recommendations that are not legally binding”.[14] This statement is quite simply false. No doubt the Prime Minister’s spokesperson, responding while Mr Cameron was on holiday in Spain, misinterpreted the word “recommendation”, because this usually does refer to non-binding decisions at the UN. After the Second World War, an increasing number of governments claimed the exclusive right to exploit the resources of the sea-bed. In 1958, a Convention on the Continental Shelf was agreed, allowing exploitation “to a depth of 200 metres or, beyond that limit, to where the depth of the superjacent waters admits of the exploitation of the natural resources”.[15] As technology developed, the 1958 Convention became obsolete and was eventually replaced by the 1982 UNCLOS. The aim of all the provisions in Part VI of UNCLOS was to stop the ever-expanding claims, to remove uncertainty and to fix boundaries. Governments would apply to the CLCS for recognition of their claims and the international community would, through the CLCS, “recommend” whether their submission does or does not “qualify”. UNCLOS unambiguously states

If the government is dissatisfied with the recommendation, it can “within a reasonable time, make a revised or new submission to the Commission”.[17] The point remains that there is only a boundary when the government and the CLCS have agreed how the UNCLOS provisions can be interpreted in the light of the scientific data. Governments have had an internationally-recognised right to exploit the continental shelf since 1958 and an agreed mechanism to define its boundary since UNCLOS came into effect. The government’s submission to the CLCS, followed by a recommendation that it qualifies, is legally binding on the two parties. The coastal state cannot later claim to extend its boundaries further out to sea and all the other states, on whose behalf the CLCS acts, must recognise the boundary that has been approved.

Restrictions on the Authority of the CommissionIt would be astonishing if a small group of geologists, geophysicists and hydrographers on the CLCS could take decisions about boundary conflicts, without any involvement of international lawyers, professional diplomats or politicians. UNCLOS clearly and explicitly forbids this possibility.

These five legal statements leave absolutely no room for doubt. The Commission must not do anything that involves any consideration of a territorial dispute or any conflict about maritime boundaries between different countries. Nothing that happens in the CLCS can have any effect upon the outcome of such disputes. The UNCLOS requirements did present a problem for governments involved in long-standing disputes. Claims for recognition of a continental shelf beyond the 200 NM minimum were to have been made within the ten-year period. This could have meant, when a dispute was settled after the ten-year deadline, no delimitation of the shelf in the disputed area would ever be recognised, for one or both of the parties. The Commission tackled this problem and at its Fourth Session adopted an annex to its Rules of Procedure, to provide options for submissions concerning disputed areas. Two or more governments can agree to make joint or separate submissions, ignoring the question of the boundaries between them. Alternatively, the Commission can consider partial submissions for undisputed parts of the shelf, leaving the disputed areas to be considered at some later date, even after more than ten years. These options still remain subject to the overriding principle that the Commission’s recommendations cannot have any effect on the outcome of a territorial or maritime dispute.

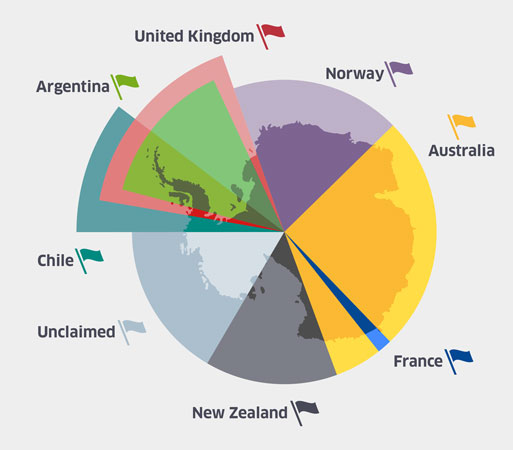

The Question of AntarcticaBefore we can consider the limits of the continental shelf in the South Atlantic, it is necessary to understand the special status of Antarctica. Argentina and Chile have sovereignty claims on segments of Antarctica, based on Spanish claims in the fifteenth century. Britain declared sovereignty over the South Orkneys and Graham Land on the Antarctic Peninsula in 1908 and today calls this area the British Antarctic Territory. The diagram below indicates how these three claims overlap and have produced a set of dormant territorial disputes. Later in the twentieth century, Norway made a large claim to protect its whaling interests and France made a small claim based on discovery. The British Empire made further claims that were inherited by Australia and New Zealand upon their gaining independence. In 1959, all seven of these governments agreed to a treaty to suspend their rights to exercise any sovereignty over the territories they had claimed. |

|

| This diagram shows the nature of the overlapping claims rather than the exact boundaries. Source: BAS et al, Discovering Antarctica |

|

At the initiative of the International Council of Scientific Unions in 1952, an International Geophysical Year was held from July 1957 to December 1958. It stimulated new research activity in Antarctica: in particular, the United States and Russia established their first, permanent, research stations. The positive achievements of the scientific co-operation across the Cold War divide made the twelve governments that had participated in Antarctica during IGY decide to ensure “that Antarctica shall continue for ever to be used exclusively for peaceful purposes and shall not become the scene or object of international discord”. They negotiated an Antarctic Treaty that was signed on 1 December 1959 and, after it had been ratified by all twelve governments, the treaty entered into force on 23 June 1961. The Treaty applies to all “the area south of 60° South Latitude, including all ice shelves”. This area is larger that the area within the Antarctic Circle, which is nearer the South Pole at approximately 66°S. In this paper, “Antarctica” will be used to mean the treaty area. Argentina, Chile and the UK were among the original twelve countries. Since 1959, an additional 41 other countries have acceded to the Treaty. Seventeen have been recognised as “conducting substantial research activity” and joined the original Consultative Parties as full participants in the annual meetings. Another 24 Non-Consultative Parties attend the meetings, but do not participate in decision-making. The treaty was extended by an Environment Protocol in 1998. Two separate environmental treaties also apply to the continent: the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals (CCAS) came into effect in 1978 and the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) in 1982. A small Secretariat was established in Buenos Aires in September 2004. These arrangements are known collectively as the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS). Antarctica was brought under a global, legal and scientific, management system.[18] The 1959 treaty agreed on “freedom of scientific investigation” throughout the continent and specified there would be exchange of information about research plans, access to each other’s research stations and free exchange of research results. The ideals of a non-political, global, scientific community were underpinned by three fundamental principles. All military activity in Antarctica was prohibited; activities under the treaty would have no effect on sovereignty claims; and each Consultative Party could appoint observers, who could have “complete freedom of access at any time to any or all areas of Antarctica”, to monitor what was happening in the research stations. In 1992, the global status of Antarctica was acknowledged, by adding a new domain name – .aq – to the Internet register of country domain names.[19] In international diplomacy, the normal way of asserting this package of provisions is to refer to the article of the Antarctic Treaty that suspends sovereignty:

The wording saves face by saying sovereignty claims have not been abandoned. Nevertheless, sovereignty rights cannot actually be exercised. Antarctica has become a global science observatory and wildlife reserve, subject to no government’s sovereignty and accessible to all.

The Antarctic Claimants Decide to Act JointlyAfter the Guidelines for submissions were adopted in May 1999, governments were very slow to complete and submit the necessary scientific work. More than five years later, Australia was just the third country to make a submission and it was the first of the Antarctic claimant states to do so. A diplomat, from one of the governments involved in discussions during 2004, said

Tensions between claimants and non-claimants arose because none of the territorial claims in Antarctica have been recognised by any non-claimant state. In addition, the US government has sent expeditions to the unclaimed sector, between the Chilean and New Zealand claims, but has never made a claim.[21b] The seven claimants had to resolve a dilemma. If they did not each make a claim for a continental shelf extending from Antarctica, they faced the risk of permanently losing any right to assert sovereignty over Antarctic maritime resources. If they did each request endorsement of a claim, they would generate widespread opposition from the rest of the world. As the Commission is composed of scientists and is forbidden to consider disputes, the goal was to find a non-controversial solution, before Australia made its submission. The Australian government spent more than a year negotiating, both with the other Antarctic claimants and with the USA and Russia, and consulted with other delegations. Discussions in New York were supplemented by visits to capitals. A delicate formula to avoid conflict was circulated as an “agreement reached on a common position regarding submissions to the Commission on the subject of the Antarctic continental shelf”. The claimants would each assert their sovereignty over the resources of a segment of the Antarctic shelf, but they would not ask the CLCS to respond. They agreed to accompany their submissions with a statement using one of the two options in the following text.

One government, Chile, did not make any submission to the CLCS and therefore it must be assumed that Chile will never gain any sovereign rights over the Antarctic continental shelf. Three of the seven governments – Australia, Argentina and Norway – made submissions that included full scientific data for a shelf extending from Antarctic territory. Australia and Norway took the first option, requesting the CLCS to take no action. The Argentine written submission made no reference to either option, but they did eventually, in an oral presentation, request no action. The remaining three – New Zealand, the United Kingdom and France – took the second option, making no submission covering Antarctica, but reserving their right to do so, at some later date. All these cases, except for Argentina, will now be examined, to provide a context for understanding the Argentine submission.

Submissions by Australia and Other Claimants to AntarcticaAustralia was, on 15 November 2004, the first of the six to make a submission that mentioned Antarctica. As had been agreed, this was accompanied by a Note Verbale, which asserted “the importance of the Antarctic system and UNCLOS working in harmony” and invoked the special status of Antarctica as an area where sovereignty has been suspended. The Australians requested the Commission “not to take any action for the time being with regard to the information in this Submission that relates to continental shelf appurtenant to Antarctica”.[21d] The Australian submission was added by the Secretariat to the agenda for the next CLCS session in April 2005. Even though the Australian government had already made the US government aware of the agreed formula, the United States quickly responded, on 3 December 2004, with a note objecting to the submission.

Similar notes followed from Russia, Japan, the Netherlands, Germany and India. The wording varied slightly each time, but the position taken was identical. In the “Introduction” to the final Summary of the Recommendations, the Commission quaintly describes these notes as “supporting” the Australian note. However, the six hostile governments were all making general statements of a much stronger nature than the Australian request to make no judgement on the claim: they rejected the claim. It was not a question of postponing consideration of the information by the Commission “for the time being”, nor accepting another partial submission could be made “later”, but the six were saying a delimitation of sovereign rights to the Antarctic continental shelf should never occur. Furthermore, they were not objecting just to Australia’s claim, but to “any State’s claim”.[22] |

|

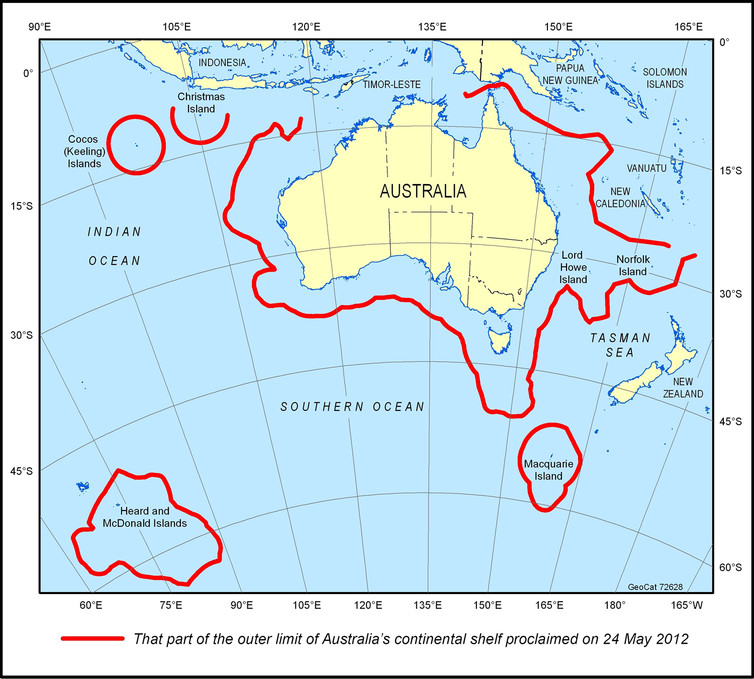

| Source: The Conversation, 29 May 2012,

“Explainer: Australia’s extended continental shelf and Antarctica”

Note that the curve at 60° S defines the Antarctic Treaty area. |

|

In response, the Commission decided to establish a sub-commission and instructed it “not to consider the part of the submission referred to as region 2”, which was based on the shelf extending from Australia’s claim on the Antarctic mainland. Nevertheless, it can be argued the Australians did manage to slip through a small violation of the Antarctic Treaty. The agreed formula solely suspended judgement on areas of the shelf based on territorial claims within Antarctica. The Australian submission also included two areas south of the Australian mainland, each with their own continental shelf area. They were a sub-maritime plateau around Heard Island and the McDonald Islands, plus an area around a sub-maritime ridge on which Macquarie Island sits. In each case, the southern most part of the claim crossed into the Antarctic Treaty area. The Commission did not discuss these intrusions into Antarctica. They were handled in the normal manner, as a scientific assessment, by the Sub-Commission on the Australian submission, and they were approved as part of the final recommendations.[23] On 4 May 2009, Norway also made a submission relevant to Antarctica, containing full scientific data “in respect of Bouvetøya and Dronning Maud Land”, (in English, Bouvet Island and Queen Maud Land). Bouvet lies north of the Antarctic Treaty area and the shelf area claimed by Norway is to the north-east of the island, so it is not covered by the suspension of sovereignty. Queen Maud Land is part of the main Antarctic land mass and does come under the Antarctic Treaty. A curious feature of the Norwegian submission is that it makes no mention of Norway’s third dependent territory, Peter I’s Island, which also lies within the Antarctic Treaty area, in the “Unclaimed” sector on the above map.[24] Norway’s submission repeated the text agreed by all the claimants in 2004 and, like Australia, they chose the first option, requesting “the Commission in accordance with its rules not to take any action for the time being” on Queen Maud Land. The Norwegian Note asks the Commission “to consider the information submitted in respect of Bouvetøya”.[25] As with Australia’s submission, the United States, Russia, India, the Netherlands and Japan made strong objections, using the same language as before. On 9 April 2010, the Commission agreed it would establish a sub-commission on Bouvet Island and it would be instructed “not to consider the part of the submission relating to the continental shelf appurtenant to Dronning Maud Land”.[26] The three countries with dormant claims that did not make a submission covering Antarctica raised the question in the context of unrelated submissions. New Zealand made its submission on 19 April 2006 and at the same time tabled a Note with the main text using text agreed by all the claimants. The Note concluded by saying New Zealand was taking the second option and its “partial submission” did not cover the continental shelf of Antarctica, but reserved the right to do so “later”, without indicating when this might be.[27] In 2008-2009, governments rushed to make CLCS submissions within the time limit and the workload of the Commission increased dramatically. The United Kingdom made several “partial submissions”, for different territories. The first one, for Ascension Island was made on 9 May 2008. Although Antarctica has no relevance to the Ascension submission, it was accompanied by a Note Verbale on Antarctica. Again, it contained the agreed text.[28] Similarly, France made a partial submission on 5 February 2009, covering two territories, the French Antilles (a set of islands in the Caribbean) and the Kerguelen Islands (in the southern Indian Ocean). As with Britain’s submission, Antarctica was of no direct relevance, but an accompanying Note Verbale repeated the arguments of other claimant states.[29] The UK and France each chose the second option of reserving the right to make a submission on Antarctica “later”. Thus, we had five governments – Australia, Norway, New Zealand, the UK and France – arguing claims to the Antarctic continental shelf might be considered in the future. They were opposed by six governments – USA, Russia, Japan, the Netherlands, Germany and India – stating claims should never be made. However, they all expressed their commitment to the Antarctic Treaty System. In effect, they were all united in saying no submission should be considered so long as the Antarctic Treaty remains in force. The statement about “the importance of the Antarctic system and UNCLOS working in harmony” can only mean that the Commission, working under the authority of UNCLOS, must not override the suspension of sovereignty in Antarctica. The Commission did not take a position on the differences between the five Antarctic claimants and the six protesters, but it did decide not to consider the submissions relating to Antarctica. Thus, the formulae, negotiated by Australia in 2004, allowed Australia and the other claimants to keep their claim alive; the objectors to deny the claims; and the CLCS to evaluate the submissions, without having to consider the deep disputes over the status of Antarctica. The British Submission on the South AtlanticThe United Kingdom made another partial submission, “in respect of the Falkland Islands, and of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands”, on 11 May 2009.[30] By this time, President Menem’s term of office had finished and Argentina had gone through a period of economic and political upheaval. Relations between the Argentine and British governments severely deteriorated, under the presidency of Nestor Kirchner, from May 2003 to December 2007, followed by Cristina Kirchner until December 2015. The deterioration was primarily due to a sustained campaign by the Argentine government to attempt to mobilise domestic and international political support for their sovereignty claim over these islands. The British government responded with very assertive statements and actions. By 2009, there was no political possibility of the two governments taking the option of making a joint submission to the Commission. In accordance with the Commission’s rules, the British acknowledged their submission covered disputed areas, in that they were “also the subject of a submission by Argentina”. In addition, they asserted

and then went on to make what had already become the standard statement of the British position.

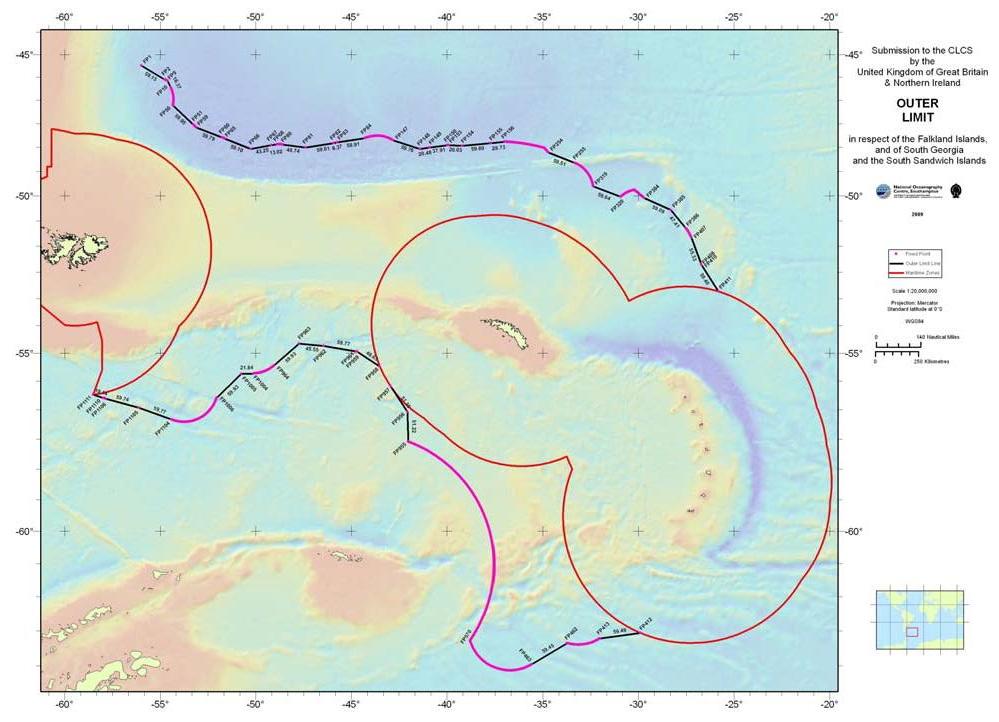

A copy of the map submitted is shown below. Much of the boundary was drawn by the criterion of measuring 60 NM from points at the foot of the slope. There were three sections where it had to be limited by the maximum of 350 NM and three by the maximum of 100 NM beyond the 2,500 m isobath. For two sections the 200 NM minimum was applied. In the west, the boundary was measured from the Falkland Islands. Then, there is a boundary around South Georgia, a narrow, crescent-shaped island, 740 NM east-south-east of the Falklands. Finally, there is a boundary around the South Sandwich Islands that are, at the nearest points, less than 350 NM further south-east and consist of eleven volcanic islands, in a chain around 215 NM long. The three boundaries overlap, so that they form a single continuous area from the most western part of the waters around the Falklands to the most southern part of the waters around the South Sandwich Islands. |

|

| Source: UK Submission to the CLCS, Executive Summary, p.5.

Note that the line of crosses, at 60° South, defines the Antarctic Treaty area. . |

|

The Executive Summary is exceptionally brief, containing just three pages of text. Much is left unsaid or implied.

Probably, discussion of points 1 and 4 was omitted in an attempt to minimise political argument with President Cristina Kirchner. If so, this tactic was successful, in that the British submission did not generate any “megaphone diplomacy” in the news media. Although the Executive Summary does not say so, there are three separate territorial disputes with Argentina: the Falkland Islands; South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands; and the location of the dormant claim to the British Antarctic Territory, totally covering the area of the dormant Argentine Antarctic claim. It is surprising that the question of Antarctica was not raised, in the CLCS proceedings, with respect to the British submission. The British map, copied above, has a sentence below it, saying

This statement is of questionable accuracy in denying the submission covers any shelf projecting from land in Antarctica. It is true that no claim is made starting from an Antarctic coastline, but part of the area, mentioned above in point 3, is “appurtenant” to the South Orkney Islands within Antarctica. The British appear to be following the precedent of the Australians, in making a claim stretching into the waters of the Antarctic Treaty area, based on islands north of 60°S. However, the British claim is a greater challenge to the Antarctic Treaty: it also overlaps a significant area of shelf defined by extension from South Orkney.[31b] Furthermore, if a boundary needs to be drawn from South Orkney, as explained in point 4 above, then why should it be a 200 NM EEZ boundary? The normal way to draw such a boundary would be between the South Orkney EEZ and the South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands EEZ. Put more generally, the submission clearly does include large areas of sea-bed within the Antarctic Treaty area. None of the six governments that protested against Australia’s submission, nor any other government, was recorded as making any comments on, let alone objections to, this aspect of the British submission. The Secretariat responded, in the normal procedural manner, by reporting receipt of the submission to all UN members and UNCLOS parties and by publishing an Executive Summary on the UN’s Division for Ocean Affairs website. The notification also said the submission will be on the agenda for the CLCS Twenty-Fifth Session, to be held in March-April 2010. On 20 August 2009, the Argentine government sent a letter to the UN Secretary-General, saying it

On 7 April 2010, a British team – consisting of Christopher Whomersley, Deputy Legal Adviser at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and Lindsay Parson, head of the Law of the Sea Group at the National Oceanography Centre, plus some advisers – made a presentation of the submission to the full Commission. The presentation made reference to the Argentine note and “firmly rejected the claim of Argentina to sovereignty over the Falkland Islands”. The chair’s report on the work of the session concluded

In summary, the CLCS refused to consider the British submission, because it covered an unresolved dispute.[33] The Commission really had no choice: the submission raised several very difficult political and legal questions.

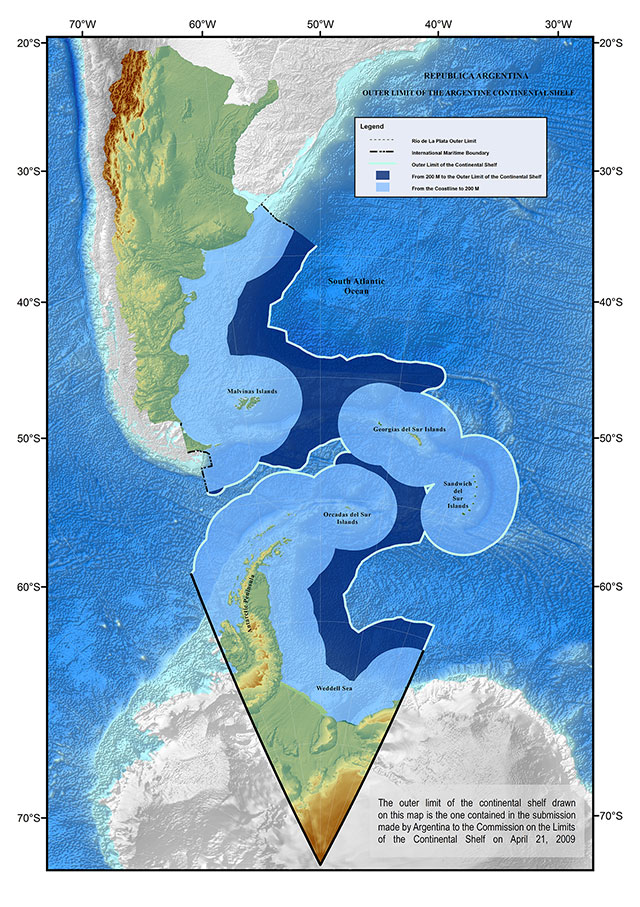

The Argentine SubmissionThe Argentine submission to the CLCS was made on 21 April 2009. It took much longer to handle, because it was administratively, scientifically and politically much more complex than the British submission. The Executive Summary started by outlining the history of Argentine policy on the continental shelf, going back to the first domestic legal action in March 1944 and recalling Argentina’s role as one of the leading countries in the development of the UNCLOS provisions. Despite its pioneering unilateral actions, the submission is firmly placed within the context of Argentina being a party to UNCLOS. The Secretariat responded on 1 May 2009, in the normal manner. Although the Argentine government had made its submission only three weeks before the British did so, this made sufficient difference for the Secretariat to place it on the agenda of the previous session of the CLCS, the Twenty-Fourth Session, held six months earlier in August-September 2009.[34] In May 1997, a law had been passed to establish the Comisión Nacional del Límite Exterior de la Plataforma Continental (COPLA) (National Commission on the Outer Limits of the Continental Shelf), under the authority of the Foreign Ministry “and also composed of” the Ministry of Economic Affairs and the Naval Hydrographic Service. Its purpose was to prepare a submission and it was supported by a variety of other government departments, along with national scientific bodies and three university departments. It should be noted that COPLA itself is an integral component of the Argentine government. In contrast, the comparable British body, the National Oceanography Centre, was at the time purely an academic body.[35] The presentation of the submission to the Commission was made on 26 August 2009 by Jorge Argüello, Argentina’s Permanent Representative at the UN; Rafael Grossi, from the Foreign Ministry; Frida Pfirter, General Coordinator of COPLA; and Marcelo Paterlini, a geophysicist; and a number of scientific, legal and technical advisers. A copy of the map, issued by COPLA for news media to illustrate the submission, is given below.[36] In geographical and geological terms, the submission can be regarded as covering several distinct areas, with a high degree of overlap between some of them.

Areas 2 and 3 overlap, as do areas 4 and 6, and also 5 and 6. The eight areas have been specified by the author, to draw attention to the politics of the submission. In political and legal term, areas 2-5 are based on territory in dispute with the United Kingdom; area 5 crosses into the Antarctic Treaty area; the EEZ south of the South Sandwich Islands crosses into the Antarctic Treaty area; areas 6-7 are based on a claim to part of Antarctica; and only areas 1 and 8 are incontestably Argentine. The submission contains eight maps drawn on a geological rather than a political basis. The maps clearly detail the location of the claimed, extended-shelf, boundary points and include labels giving the legal and geological basis for plotting the points. |

|

| Source: COPLA, “Continental Shelf Map” web page. |

|

The Argentine Position on Disputed BoundariesAfter the formal introductory materials, the Argentine Executive Summary is divided into three substantive sections.

Both sections G and H were acknowledging that Argentina must conform to the provisions of UNCLOS and the Commission’s procedures for handling disputed areas. In particular, on the border with Uruguay and on the two disputes about islands currently under British rule, Annex I of the Rules was explicitly invoked. After a surprising delay of more than three months, the UK took up these questions and tabled a Note, on 6 August 2009, asserting its sovereignty over the islands.

Three weeks later, during the Argentine delegation’s oral presentation on 26 August 2009, Mr Grossi objected to the British Note. He also repeated the statement that there was an area under dispute. The Commission had accumulated too many submissions to set up a sub-commission on the Argentine submission at this point. Nevertheless, it took the decision that it would go ahead, when Argentina reached the head of the queue. It also decided what would be its instructions to the sub-commission. The chair’s report on the work of the session concluded

In summary, the formal decision on the Argentine submission in August 2009 with respect to the islands was exactly the same as it would be eight months later on the British submission (see above). The Commission acted in accord with the British suggestion that it should ignore those parts of the Argentine submission related to the Falkland Island and to South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. In effect, the Argentine submission and the delegation’s presentation had given the Commission no choice, because they had accepted there was a dispute.[38]

The Argentine Position on AntarcticaAn extraordinary feature of the Argentine submission is that the Executive Summary makes no mention of the Antarctica Treaty nor of the question of suspended sovereignty. Like the Australian and the Norwegian submissions, the Argentine submission was accompanied by a Note Verbale. This did not follow the precedent of the other claimants, using texts that were identical to each other. The Argentine Note of 21 April 2009,

The above text corresponds partially to the “agreement reached on a common position” by the seven Antarctic claimants, including Argentina. Crucially, unlike the Australians and the Norwegians, the Argentine Note did not directly request the Commission “not to take any action for the time being”, as it was obliged to do by the agreement. As was discussed above, Article IV of the Antarctic Treaty provides for the suspension of sovereignty and the Rules of Procedure of the CLCS dictate that no consideration should be given to any area that is subject to a territorial dispute. It could be argued that, in effect, the reference to Article IV of the Antarctic Treaty implied acceptance that no action would be taken, but at this point the Argentine submission still formally required a response on a claim to an Antarctic shelf. It cannot be argued that circumstances had changed in the four years since the common position had been agreed, because, just two weeks later, the Norwegians made a similar submission based on their Antarctic claim and followed the common position with precision. The Argentine government clearly violated its commitment made in the agreement with the other claimants. Before the Commission met to consider the Argentine submission, the United States and Russia each issued protest notes against the inclusion of an Antarctic claim. India, the Netherlands and Japan did so shortly afterwards. The British note of 6 August 2009 also covered the question of Antarctica and a position close to the protesting states was taken.

It would appear that the pressure from the United States, Russia and other governments made the Argentines realise they could not attempt to hold out on Antarctica. During the oral presentation to the Commission, the Argentine delegate, Mr Grossi, referred to the Argentine Note, but went further by coming close to the formula from the claimants’ agreed common position. He did not explicitly request no action, but he did acknowledge

The outcome was a clear rejection of the attempt in the Argentine Executive Summary to ignore the impact of the Antarctic Treaty.

In summary, the initial Argentine attempt to disregard their commitment to the six other claimants, under the “agreement reached on a common position” had to be abandoned. Mr Grossi did accept that the Argentine submission on Antarctica would not be assessed. The formal decision by the Commission in August 2009 on the Argentine submission was exactly the same as it had been in April 2005 on the Australian submission and would be in April 2010 on the Norwegian submission. The common position of the claimants, the Commission’s previous decision, the text of the Argentine Note, the protest notes and the statement by Mr Grossi are of equal importance to the Executive Summary in interpreting the Argentine submission and the nature of the subsequent decision by the Commission. In other words, the Commission again had no real choice and it decided to ignore those parts of the Argentine submission related to Antarctica.

The Work of the CLCS on Argentina’s SubmissionArgentina’s submission eventually came to the head of the queue during the Thirtieth Session of the Commission and, on 2 August 2012, a sub-commission was appointed. In view of the time that had passed since the first presentation and the change in the membership of the CLCS, Argentina was allowed, on 8 August, to make a second presentation. This time the delegation was led by Mateo Estrémé, temporary head of the Argentina’s Permanent Mission to the UN. He reiterated the arguments about the islands controlled by Britain and tabled a brief Note objecting to the British arguments made in 2009. Mr Estrémé finally, acted in accord with the claimants common position and made an explicit, direct, Argentine request to the CLCS not to take any action on Antarctica. The Commission reiterated its instructions to the sub-commission not to consider the disputed areas nor Antarctica.[42] The sub-commission worked on the submission from August 2012 to August 2015, during nine sessions of the CLCS. In this time it had a total of 38 meetings with the Argentine delegation, in order to gain additional data and verbal information. During the Commission’s Thirty-Eighth Session, on 15 August 2015, the sub-commission presented its conclusions to the delegation and a week later formally approved its Recommendations by a majority vote. They were then approved by the full Commission on 11 March 2016 and sent to the Argentine government on 28 March.[43]

The Commission’s Final Recommendation on the Argentine SubmissionThe Argentine Foreign Ministry issued a press statement on 27 March and held a press conference on 28 March claiming the full Argentine submission to the Commission had been approved. The Foreign Minister, Susana Malcorra, was overseas, but she made a presentation via a video link and said

The Deputy Foreign Minister, Carlos Foradori, chaired the presentation and said

There is some ambiguity on what areas of continental shelf might correspond to the wording of these triumphant statements. There is no ambiguity when we examine the COPLA statement on its website’s home page.

Finally, various stories in the Argentine press demonstrate they thought the Commission had endorsed the complete Argentine submission.

These stories make it absolutely clear that COPLA and the Argentine Foreign Ministry were presenting a mistaken account of the Commission’s recommendation. On 28 March La Nación and Clarin each presented the COPLA map, used at the Foreign Ministry press conference, with a heading that unambiguously implied the full submission had been approved by the CLCS. Similarly, the Herald included the following map, taken from the Executive Summary of the submission, without any hint that the shelf around the islands and in Antarctica had not been endorsed.[44] |

|

| Source: Buenos Aires Herald, 28 March 2016 Gov't presents new map after UN approved expansion …. |

|

Given the incorrect presentation at the Foreign Ministry press conference and the false stories in the Argentine media, it is not surprising the British media also produced headlines falsely asserting the United Nations had endorsed Argentina’s claim to sovereignty over the Falkland Islands.

The only newspaper that seems to have properly checked the story and written a correct interpretation is Penguin News, the weekly A4-sized local paper, produced in the Falklands. Their headline, on 1 April 2016, was

Penguin News had an accurate news story, because they had used the UN Press Release covering the Commission’s report on its work.[45]

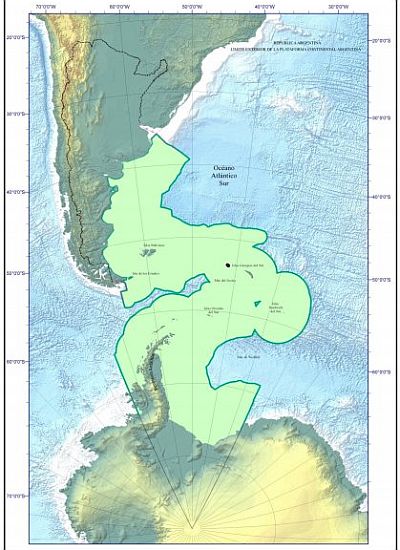

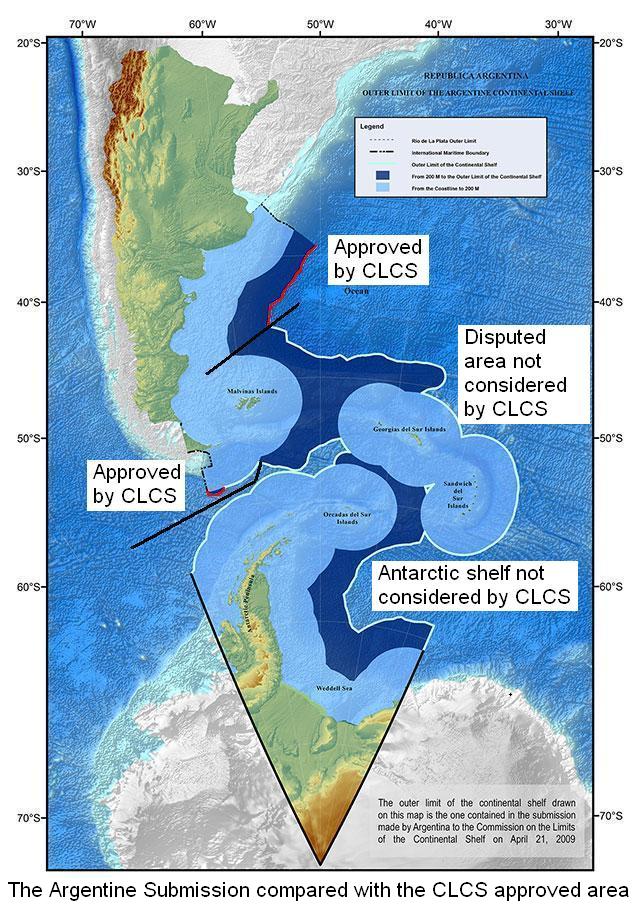

What the Commission Actually RecommendedThe final stage of the work of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf is to make public a Summary of the Recommendations on its website and this was done on 23 May 2016. The Summary starts with an Introduction, giving the history of the decision-making process in the Commission; reports what documents the Argentines submitted; and then outlines the work of the sub-commission. The title for the next section detailing its conclusions is

Leaving aside the geological description, we can see Section IV is dealing solely with the continental shelf protruding from the northern part of the Argentine mainland and from the southern coast of Tierra del Fuego and Staten Island. Section II describes how the Commission, (as explained above in this paper), instructed the sub-commission not to consider any other part of the submission. There are no recommendations on the shelf around the islands nor on Antarctica. At the end of the Summary, Table 3 reports all the co-ordinates from Rio de la Plata up to RA-481 and Table 4 reports all the co-ordinates, from RA-3458 to RA-3840, for the Tierra del Fuego margin region. Figure 3, copied below, provides two maps showing these boundaries. These two maps endorsed by the Commission differ very substantially from the previous map publicised by the Argentine Foreign Ministry.[46] |

|

| Source: CLCS, Summary of the Recommendations, 23 May 2016. |

|

The extent to which the Foreign Ministry mis-reported what had happened can be seen by comparing the COPLA map publicised on 28 March and the maps published in the Commission’s Summary of the Recommendation. However, it is not easy to make a direct comparison, so I have created a new map, which is shown below. I started with the COPLA map and then added, in red, the boundaries endorsed by the Commission, along with explanatory text.[47] |

|

| Source: COPLA plus CLCS, Summary of the Recommendations, 23 May 2016. |

ConclusionWhen the Commission decided in August 2009 to refer the Argentine submission to a sub-commission, the Argentine Foreign Ministry knew no part of the continental shelf around the islands under British control would be considered by the sub-commission. Equally, it knew that the sub-commission had been instructed not to consider the Argentine claim to an Antarctic continental shelf. The Argentine government had been forced to accept that, under the terms of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the Antarctic Treaty and the mandate of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, its submission would not and could not be approved in full. Indeed, the legal situation was so unambiguous that the Argentine delegation did not even ask for the full submission to be considered. Argentine diplomats were involved in the Australian negotiations aimed at preventing the Commission discussing Antarctica. They were in 2004 party to the agreement on a common position with the other Antarctic claimants. Two senior diplomats and the head of COPLA (an agency of the Foreign Ministry) were present at the Commission in August 2009, when the decisions were taken to instruct the sub-commission to give no consideration to the parts of the submission related to disputed territories and to Antarctica. Another senior diplomat was present in August 2012, when these decisions were confirmed. Several others at the UN and in Buenos Aires would have dealt with the delineation of the continental shelf during the long process of working on the submission. The question arises, why did senior professional staff in the Argentine Foreign Ministry allow ultra-nationalist illusions to continue for over six and a half years. An even more important question for the Argentine political system is to ask why the Foreign Minister, Susana Malcorra, and her Deputy, Carlos Foradori, were so misled by the diplomats. The South Atlantic Council was formed to promote communication between Argentines, British people and Falkland Islanders, in order to seek co-operation and understanding that might eventually lead to a peaceful settlement, to the Falklands/Malvinas dispute, acceptable to all three parties. Neither Britain nor Argentina can separately gain any internationally recognised rights to exploit the resources of the continental shelf, in the south-west Atlantic, so long as the dispute continues. On the other hand, the Commission could endorse a joint submission, if the governments of Argentina and the UK were willing to agree pragmatic arrangements to share the resources. This story demonstrates how pointless it is to continue with ritualised conflict, based on a nineteenth century idea of sovereignty.

CitationPlease cite this paper as

For further reading on sovereignty, see SAC Occasional Paper No. 11,

|

A Note on the Update in September 2016After this paper was first published in May 2016, the Chilean government submitted a Note Verbale to the CLCS that was published on its website. This provided the text of an agreement reached, at the initiative of the Australian government in late 2004, by the seven Antarctic claimant states. Consequently, a new section, The Antarctic Claimants Decide to Act Jointly has been added to the paper. Thereafter, references to the “Australian text” have been changed to the “text agreed by the Antarctic claimants” or some similar wording. Finally, the point that Argentina broke this agreement has been made. In addition, the updated version makes a correction to distinguish between the area within the Antarctic Circle and the larger area covered by the Antarctic Treaty. Several footnotes have had supplementary references added, notably to include more links to documents in Spanish.

CitationPlease cite this paper as

© South Atlantic Council, and Peter Willetts, May and September 2016. |

|

All papers in this series (including both web page and PDF versions) are available at www.staff.city.ac.uk/p.willetts/SAC/OCPAPERS.HTM. (The capital letters in this URL must be used). Any text on this website may be freely used provided that (a) it is for non-commercial purposes, (b) quotations are accurate and (c) the South Atlantic Council and the website address - www.staff.city.ac.uk/p.willetts/SAC - are cited. Page maintained by Peter Willetts [P dot Willetts at city dot ac dot uk]

Second Draft 28 May 2016: final map added. |